Charting India's path in an evolving world

Guest Interview with Niranjan Rajadhyaksha, Executive Director Research and Strategy at Artha Global and author of the award-winning Cafe Economics column in financial daily Mint.

India’s economic future continues to be hotly debated, not least because of Prime Minister Modi’s vision to make it a developed economy by 2047. Whether and how a ‘Viksit Bharat’ can be achieved has become central to discussions about the country.

Unfortunately, economic trends haven’t played along. The stellar post-pandemic growth recovery has given way to an abrupt slowdown, led by falling private consumption growth. Now, India’s ambitions to become a manufacturing exports powerhouse are threatened by a protectionist US administration and a fragmented global market. Meanwhile, other challenges such as climate change continue to loom in the background. What does this mean for India’s long-term economic prospects? Will it become the economic power it aspires to be and many hope for?

I was delighted when Dr. Niranjan Rajadhyaksha agreed to untangle these issues for AD’s readers. Niranjan heads research and strategy at Artha Global, which is a globally networked policy consulting organization. Prior to that he had an illustrious career in journalism and academia. Winner of the prestigious Ramnath Goenka Award for Excellence in Journalism and the Society of Publishers in Asia Awards for excellence in opinion writing more than once, his list of accomplishments is long. Niranjan’s widely read op-eds consistently provide engaging commentary on complex economic issues, with a sprinkling of economic history guaranteed to pique readers’ interest.

It gives me great pleasure to share his insights on India with you.

“A (6.5%) growth rate will mean greater heft in the global economy, given India’s sheer size.

The problem is that the truly successful economies of East Asia (including China) were clocking double-digit growth when they were at the stage of development that India is at right now. So there is a good case to ask how India can accelerate from here…” - Niranjan Rajadhyaksha

Priyanka: Thank you for joining us Niranjan. Let’s start by talking about the recently announced FY26 (year starting March 2025) budget. It comes against a backdrop of weak labour market, slowing GDP growth and challenging external environment. Do you think that the government has delivered sufficient demand stimulus with the income tax cuts to revive consumption and spur growth?

Niranjan: The cut in the tax on personal incomes is a response to concerns in recent quarters about weak consumer spending, which has been the mainstay of aggregate demand in India. The finance minister has said that the tax cut will effectively put an extra Rs 1 trillion in the hands of Indian households. That is around 0.2 percent of the estimated GDP for FY26. Most estimates of fiscal multipliers for India show a tax multiplier of -11, which means that a 0.2 percent of additional disposable income should broadly result in a similar increase in GDP. So the impact will be modest.

Some of the recent context also matters. The size of any fiscal multiplier is sensitive to how much of the additional income is saved rather than spent. India has seen a rise in household leverage in recent years, and not all of this has been to buy assets such as houses. Unsecured loans to smoothen consumption have also been important. One concern would be that households use the extra money in their hands to pay off debts rather than spend it on goods and services.

Consumer demand was strong in the two years after the pandemic because households at the upper end of the income pyramid had a stock of excess savings that could be spent down. My own view is that the challenge over the medium term is to increase labour incomes in India, through the creation of more quality jobs as well as higher wages. Job creation in India has been weak. And real wages of the wider labour force have been stagnant since well before the pandemic. Companies are unlikely to invest in new capacity unless there is more clarity on consumer demand in the coming years.

Priyanka: Under the Modi administration, government expenditure has become an important driver of growth. However, for central government’s debt to fall to 50% of GDP by FY31, more public spending may have to be reined in, including on capex. Do you see that as a challenge for India’s longer-term growth outlook?

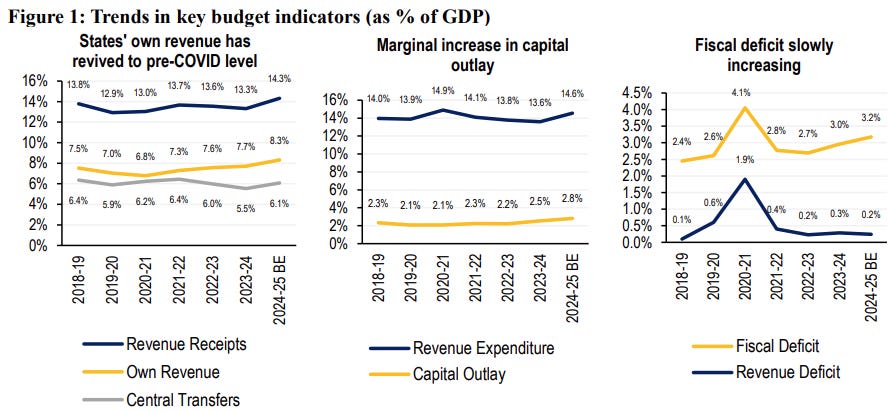

Niranjan: The Modi government deserves credit for sticking to the post-pandemic fiscal correction path that was announced in 2021. It also improved the quality of its spending by allocating more money for infrastructure, for which the multipliers are far higher than those on revenue expenditure or lower personal income tax rates. Its intent on the fiscal front is very clear. The decision to switch from the annual fiscal deficit to a public debt ratio target over the next five years will give the government more flexibility to respond to fluctuations in the business cycle.

My own assessment is that the pace of fiscal consolidation will need to be slower than what we saw in the past four years, assuming the Indian economy grows at over ten percent in nominal terms. However, the fiscal impulse will continue to be negative. That will weigh a bit on economic growth, but I doubt it will hurt India’s long term growth prospects. For that, issues such as a strong private capex cycle and jobs creation are far more important.

The state of subnational finances also matters in the Indian macro story. State governments collectively spend more than the central government. There is a wide dispersion in the fiscal health indicators of Indian states, with some states being managed well while some are inching towards a fiscal cliff. This is an issue that needs to be watched closely in the coming years.

“…the fiscal impulse will continue to be negative. That will weigh a bit on economic growth, but I doubt it will hurt India’s long term growth prospects. For that, issues such as a strong private capex cycle and jobs creation are far more important.”

Priyanka: Staying on India’s growth strategy, is the pivot towards export-led manufacturing sustainable in the long run given a more protectionist external environment and the significant dependence on China for inputs?

Niranjan: The darkening clouds over the multilateral trading system are definitely a cause for worry, especially at a time when India is trying to pitch for a greater share of the global supply chains that are expected to diversify away from China. One misconception is that the Indian economy is insulated from global trade shocks because it depends on domestic demand. But the record shows that the Indian economy actually accelerates whenever exports grow rapidly, as we saw during the booms of 1993-96 and 2004-08. And external demand in both these episodes stimulated an increase in domestic private sector capex.

A lot now depends on how the world adjusts to the Trump threats2. One possibility is that other countries join hands in strengthening regional trade agreements. Trade diplomacy will matter a lot for market access if the time-tested multilateral trading system is undermined.

However, India has consciously chosen to stay out of regional trade deals such as Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). I think it is time to reconsider some of these decisions. Many other FTA negotiations have not progressed as initially expected. One strategic decision that the Indian government needs to make is whether it wants to connect more with the trade in intermediate goods that is dominant in Asia or to geographies of final demand such as the US and Europe.

The geopolitical winds are aligned well for India, so this would be the wrong time to become more protectionist. There is also the broader political economy question about why large Indian conglomerates tend to invest in non-tradable sectors such as telecom, finance, retail and infrastructure, rather than in the tradable sectors such as manufacturing.

Priyanka: India experienced its longest heat wave in 2024, and extreme climate events are on the rise. To what extent are India’s economic prospects hampered by climate change?

Niranjan: Climate change is undoubtedly a risk. Nearly half the Indian labour force works outside in the hot sun. Some of the corporate commentary during the heatwave of 2024 showed that companies had to halt work at project sites because the workers were exhausted3. Micro-finance companies reported a rise in loan defaults because the incomes of their borrowers were affected during the heat episode. Pranjul Bhandari of HSBC has done econometric work to show that food inflation in India is now more sensitive to heat shocks. Besides this, some 170 million Indians live along the coastline, including in some of the most dynamic cities.

India has committed to becoming a net zero country by 2070, but the more immediate challenge is to design transition paths in key sectors such as energy, industry and transport. The urban policy team I work with at Artha Global also makes the point that the climate transition in India has a spatial aspect as well4. India is still building its cities so there is an opportunity to build for a world with higher temperatures. Urban form, building design and public transport can play a big role in the green transition in India, unlike in cities which have to focus on adaptation since they have already been built.

Priyanka: India’s goal to become a developed economy by 2047 is met with equal parts enthusiasm and scepticism. Leaving aside timelines, how do you see India’s role developing in the world order?

Niranjan: The Indian economy has averaged a growth rate of around 6.5 percent since 1992. This can broadly be assumed to be the sustainable growth rate for the country for at least another decade. Such a growth rate will mean greater heft in the global economy, given India’s sheer size.

The problem is that the truly successful economies of East Asia (including China) were clocking double-digit growth when they were at the stage of development that India is at right now.

So there is a good case to ask how India can accelerate from here5, rather than being satisfied with the fact that it is currently growing faster than countries that are closer to the global productivity frontier. That will depend on a series of policies needed to support three ongoing transitions - from rural to urban, from agriculture to industry and services, and from informal to formal enterprises. All three can support productivity growth if managed well.

Priyanka: What books would you recommend to AD’s readers on the Indian economy?

Niranjan: Here are some books I like. It is not an exhaustive list.

Accelerating India’s Development, by Karthik Muralidharan

Advice and Dissent: My Life In Public Service, by Y.V. Reddy

India’s Political Economy 1947-2004: The Gradual Revolution, by Francine Frankel

India's Long Road: The Search for Prosperity, by Vijay Joshi

In Service of the Republic: The Art and Science of Economic Policy, by Vijay Kelkar and Ajay Shah

Priyanka: Thank you!

See National Institute of Public Finance and Policy working paper, ‘Fiscal Multipliers for India’, 2013

See Mint op-ed, ‘India must not let Trump’s tariffs and trade disruption weaken its export thrust’, 18 February 2025

See Artha Global report, ‘How India Copes with Heat’, September 2004

See Artha Global report, ‘Localising Green Transitions in India’, May 2022

See Artha Global report, Niranjan et. al. ‘The Road to Viksit Bharat @ 2047’, December 2024